When Talk Gets Us Nowhere

Last year, I attended city council meetings watching Councillors make difficult-to-reverse decisions that would affect us all. I was following a bylaw amendment. The weeks passed, and as I spent long evenings in hot rooms, I lost confidence in the process.

It was clear that we were all crucially discussing something slightly, and occasionally, startlingly different. Sometimes the voices of those least affected were loudest. Councillors channeled their creativity into fantasies about what could go wrong rather than responding to expressed needs and desires. Proposed alternatives proved too hard to imagine, as they often do. As the ideas grew more contentious, people flung around more loaded keywords: ‘security’, ‘sustainability’, ‘public health risk’, and most abused, ‘innovation.’ There was absolutely no chance these discussions would yield an innovation. It was difficult to discuss things that already existed, never mind options requiring imagination and shared vision.

Two Approaches to Getting User Input

Words are a limiting way to share a vision. In design, making things visible and tangible as early as possible is a way to invite others into an idea, so we can stop debating at an ideological level and focus on the choices that actually shape interactions and outcomes.

In my past work, being collaborative meant agreeing on ideas together (often in meetings and always with words). We generally delegated the ‘making it real’ part to a smaller group, who would plan and implement.

At the end, we would have something to offer to end users, but it would be kind of a fait accompli and we hoped they liked it. From there, we were in a world of quality improvement that relied on surveys to get user input. We did not test our assumptions with users, only our implementation.

Co-design uses prompts to aid the imagination

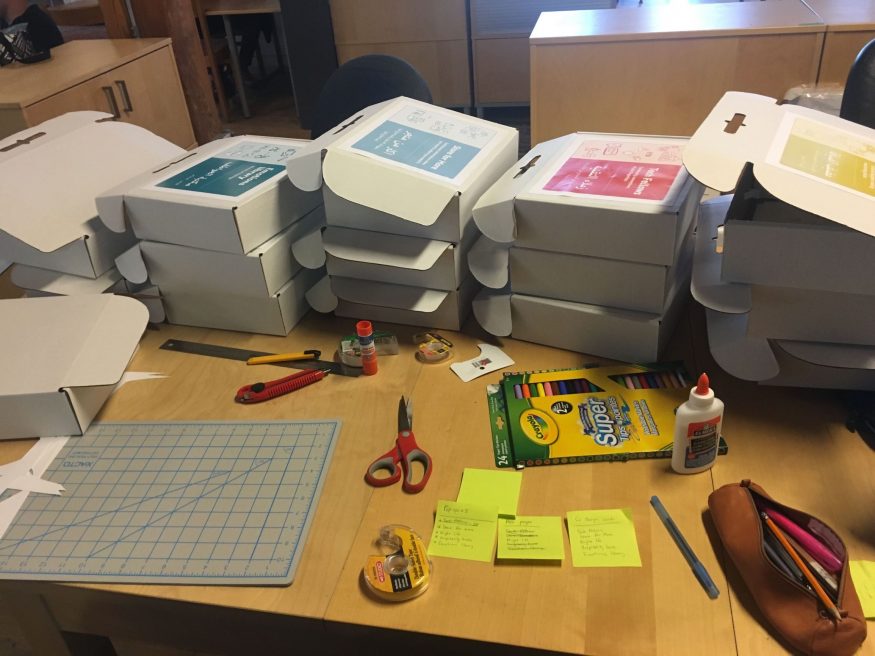

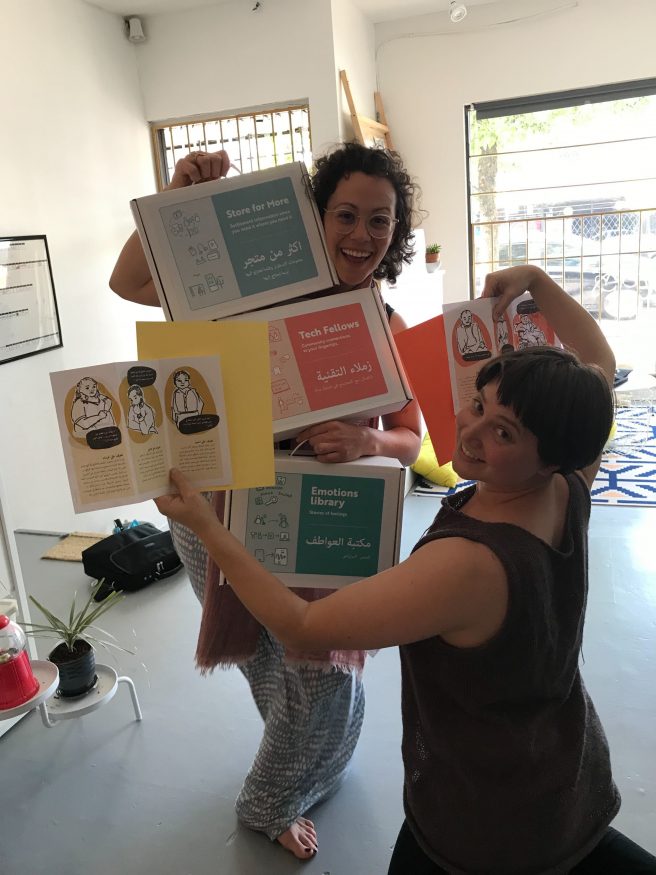

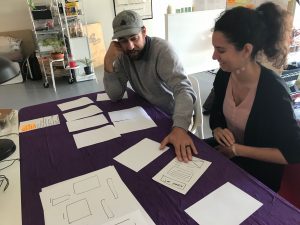

In late May, our bi-coastal teams came together over two sprints. We worked on our invitation to end users to be part of the process in a very different way, through co-design.

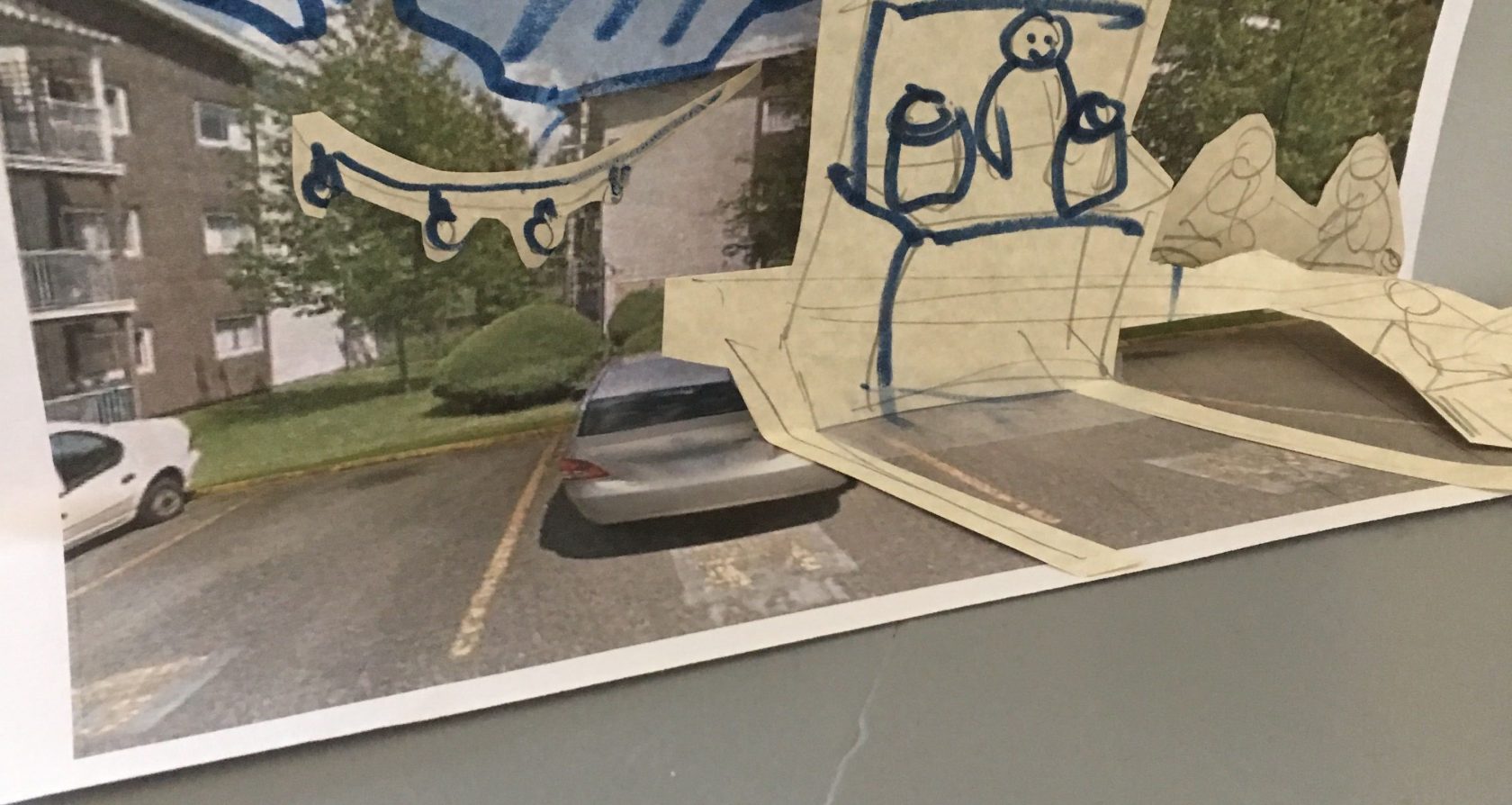

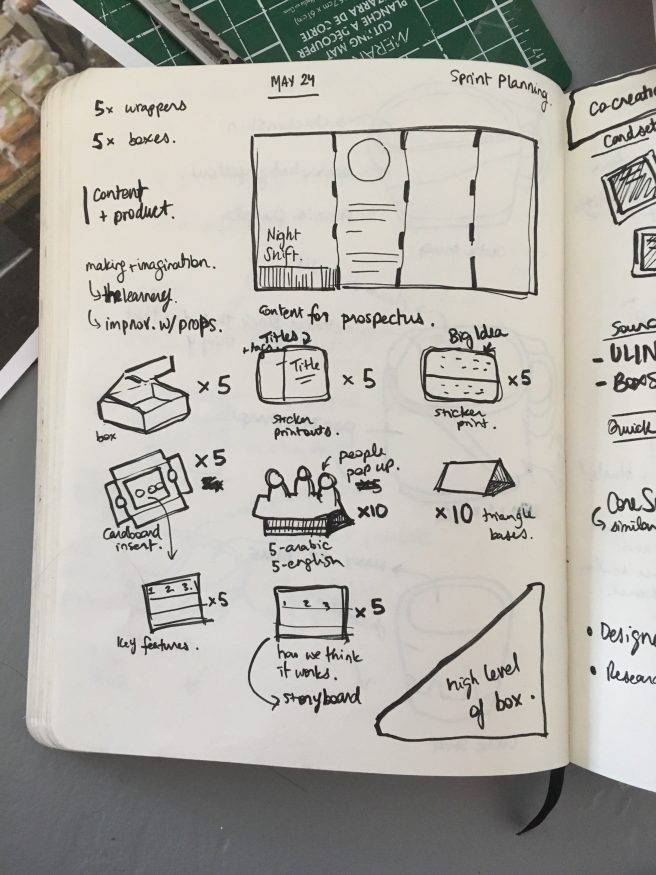

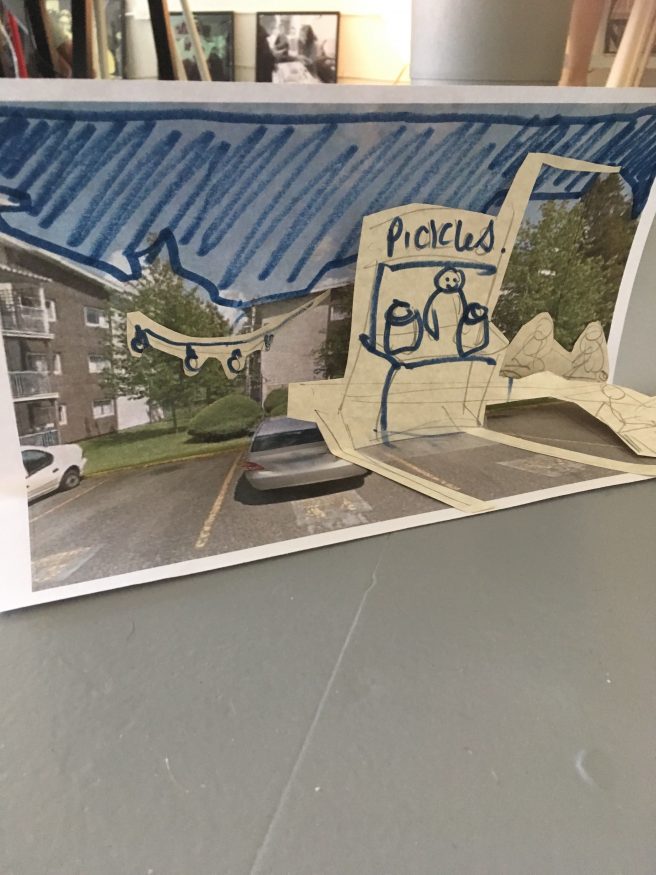

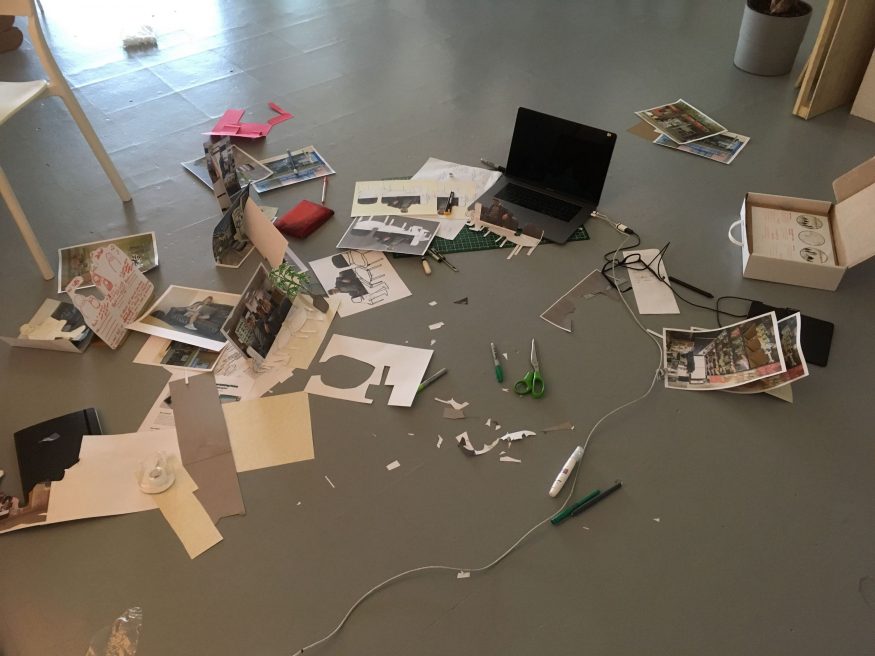

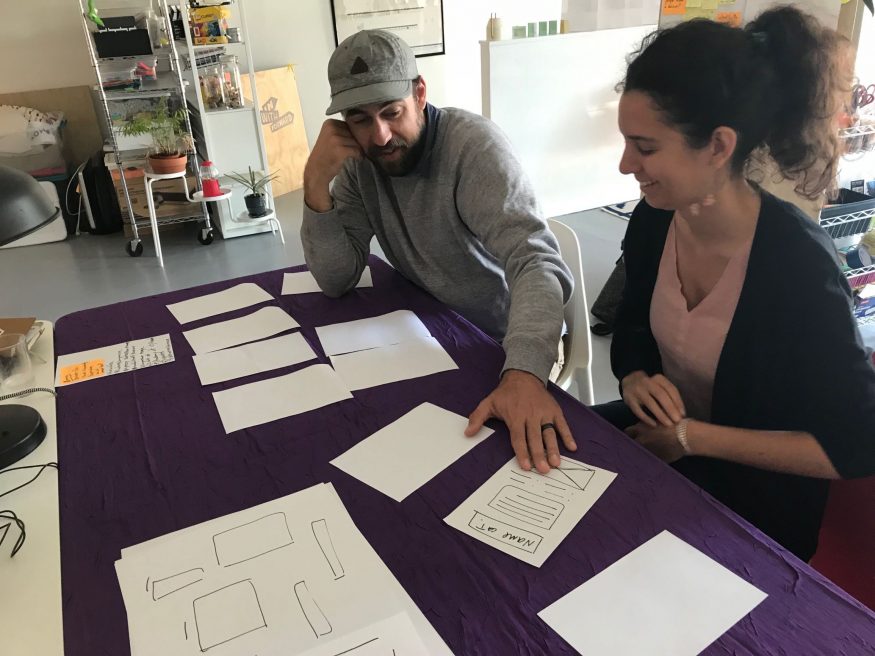

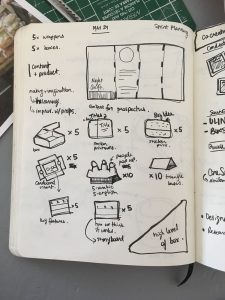

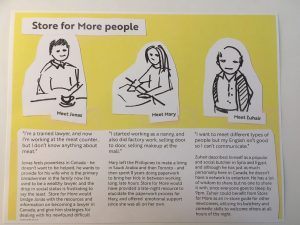

We took five ideas that were mostly described on paper, and in a few short storyboards. From there, we turned them into something people could interact with, make choices about, and understand through both narrative and pictures. We wanted end users to have enough to be able to tell us what felt believable and what didn’t, how something might happen (and how it certainly wouldn’t.) The goal of prototyping is to make mistakes and learn early, before getting into a more resource intensive stage. We worked with cardboard, paper, and glue.

Faking It for Co-Design

Co-design is a little ‘fake it ’til you make it’, balanced carefully with a nothing’s-precious attitude. If the idea is too great an imaginative leap for people, they either cannot engage, or they drag it back into the realm of the familiar. There, we end up reproducing something they’ve experienced before – not because it was so great, but because it’s so easy to picture. Once people can imagine something, they are more likely to engage with it and suggest alternatives. It helps if it doesn’t look too polished.

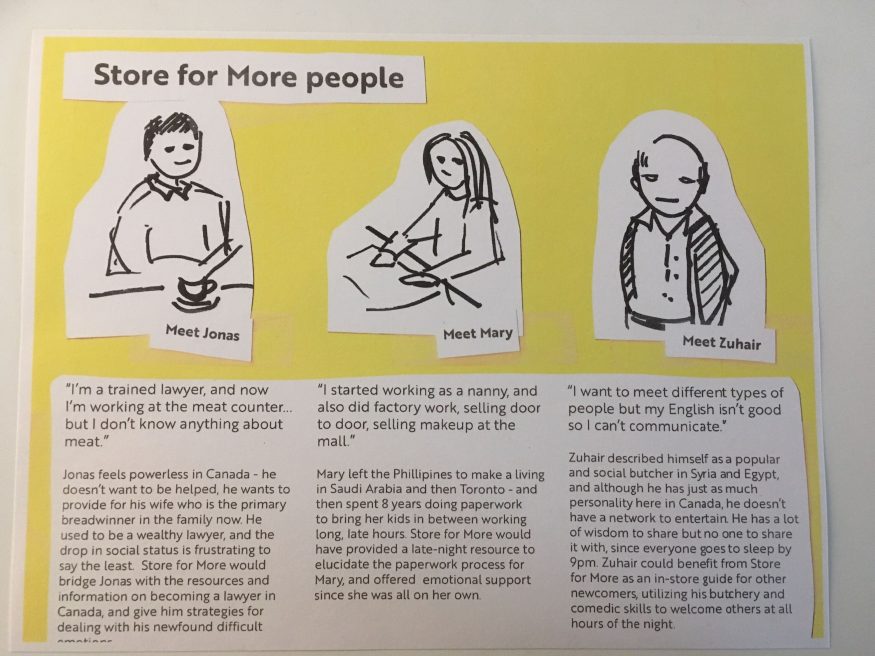

For each idea we aimed to provide enough to help people envision it, and then produce a series of options around the kind of people or roles that might be involved, where it would take place, and what exactly might be on offer. For example, we imagined multiple settings where a core interaction, like selling goods from a micro business might take place. Then we can ask which, if any, seem most likely and why.

All The Benefits of Co-Design

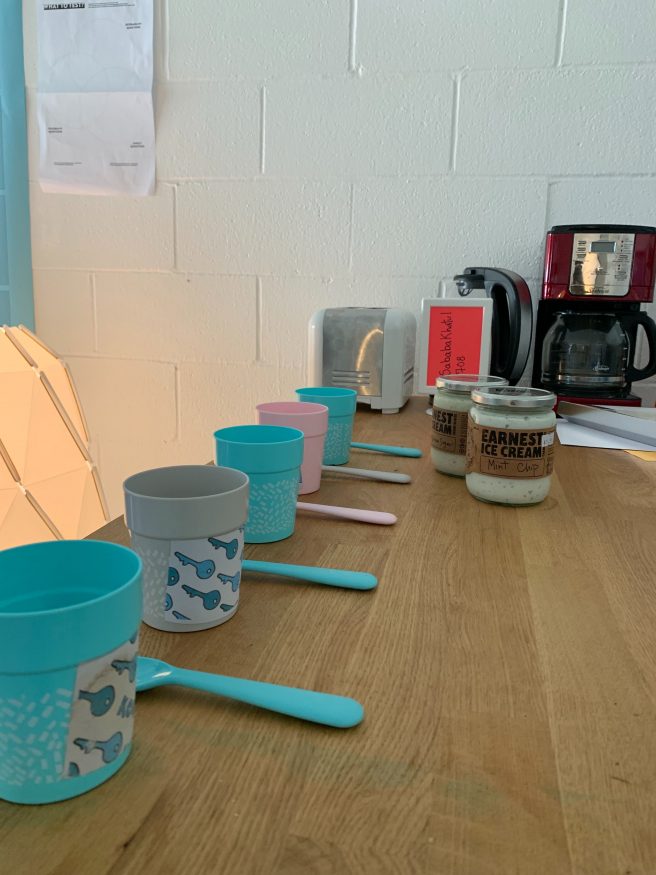

Our North York Community House (NYCH) crew scheduled the first co-design session for 3PM on the last day of the sprint. Boy did that make us move! We focused on having one or two of five idea boxes ready to share. What did get out of it?

- Bringing others into our ideas makes them feel more real and builds energy after an exhausting sprint

- Quick feedback to incorporate before we invest scarce time and money into other boxes and co-design sessions

- Relationships and champions – our co-designers expressed interest in playing roles in the solution they tested, and continuing to co-design with us

- Co-designers were able to express when something wouldn’t work for them, didn’t interest them, or seemed highly improbable

- Co-designers introduced new language, cultural contexts, scenarios, and props to help us communicate and bring the ideas alive for others

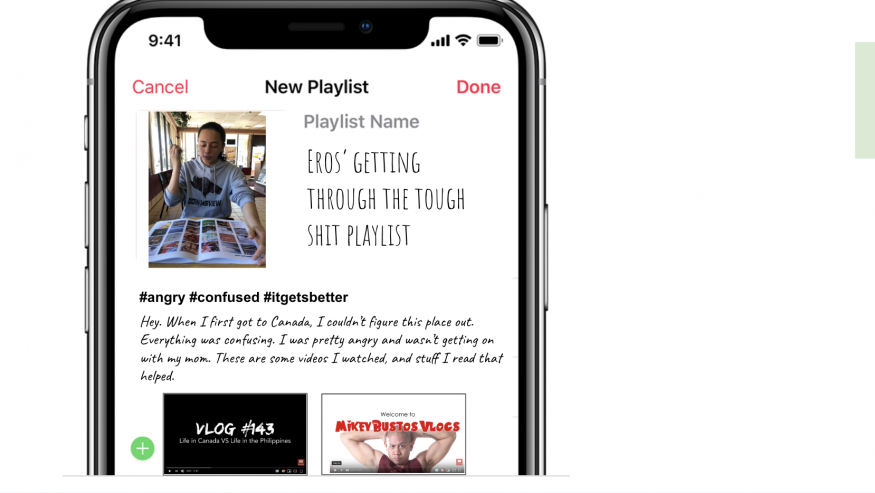

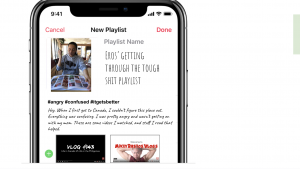

Come the end of June, we’ll have more substantial data from co-design, to help us iterate and build-out our ideas. Currently, they still mostly live on paper, albeit in pop-ups, and cut-outs, with touchpoints a bit like those people interact with when selecting a service. Our next move will be to start enacting more interactions and mocking up content like job descriptions and that playlist about “getting through tough shit.” We’ll keep you posted.