Categories

Ko is looking for a sense of place, adventure, and self. He feels lost. He wants to build his social status, which for him means getting off benefits, sorting out his debt, and having a respectable place to live. But he also doesn’t want to feel tied down. He’d love to be able to travel, and to forge some new relationships.

Addressing Ko’s housing problem is very different from addressing his social status. Moving Ko into housing won’t address some of the loneliness and disappointment that has fed his prior drinking. Nor will it address some of the barriers to him staying housed – like the thousands of dollars owed to banks, and his last work situation that didn’t end so well.

Working backwards from the outcomes that matter to people like Ko is at the root of our approach to grounded change.

It’s not easy to do. Social services are programmed to work from what the system thinks is best for people – and can (at times) insidiously cloak its outcomes in the language of person-centeredness and individualization. Disrobe the language of personal choice, and you’ll find plenty of uncontested ideologies and outdated theories.

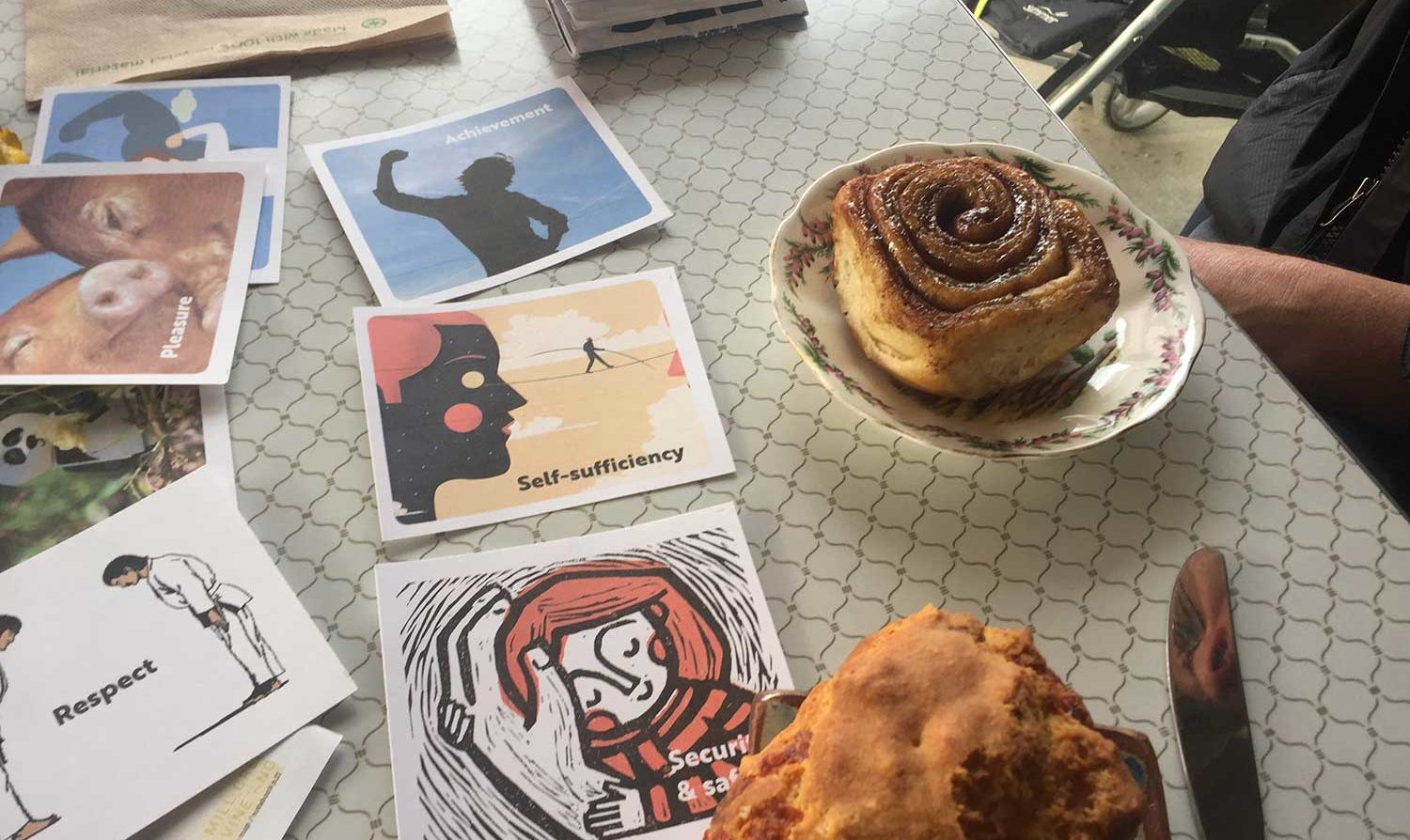

The welfare state emanates from a charity mindset, which says people on the margins should be grateful for basic supports. Couple that with the stronghold of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, and you get the commonplace belief that food and shelter must come before love, belonging, esteem, purpose, and meaning.

For Ko, his need for shelter and esteem are deeply intertwined. When we’re only attentive to the first need, we inadvertently act in ways which compromise the later need. Stick him in a subsidized housing complex, alone, without tools to make amends to his prior employer, and he’s likely to stay in his shell – at high risk of drinking. Broker him to a shared house with other book lovers, coach him on his debt, and help him to find a purpose and Ko is much more likely to thrive.

Most innovation processes are agnostic about outcomes, instead jumping into problem-solution mode.

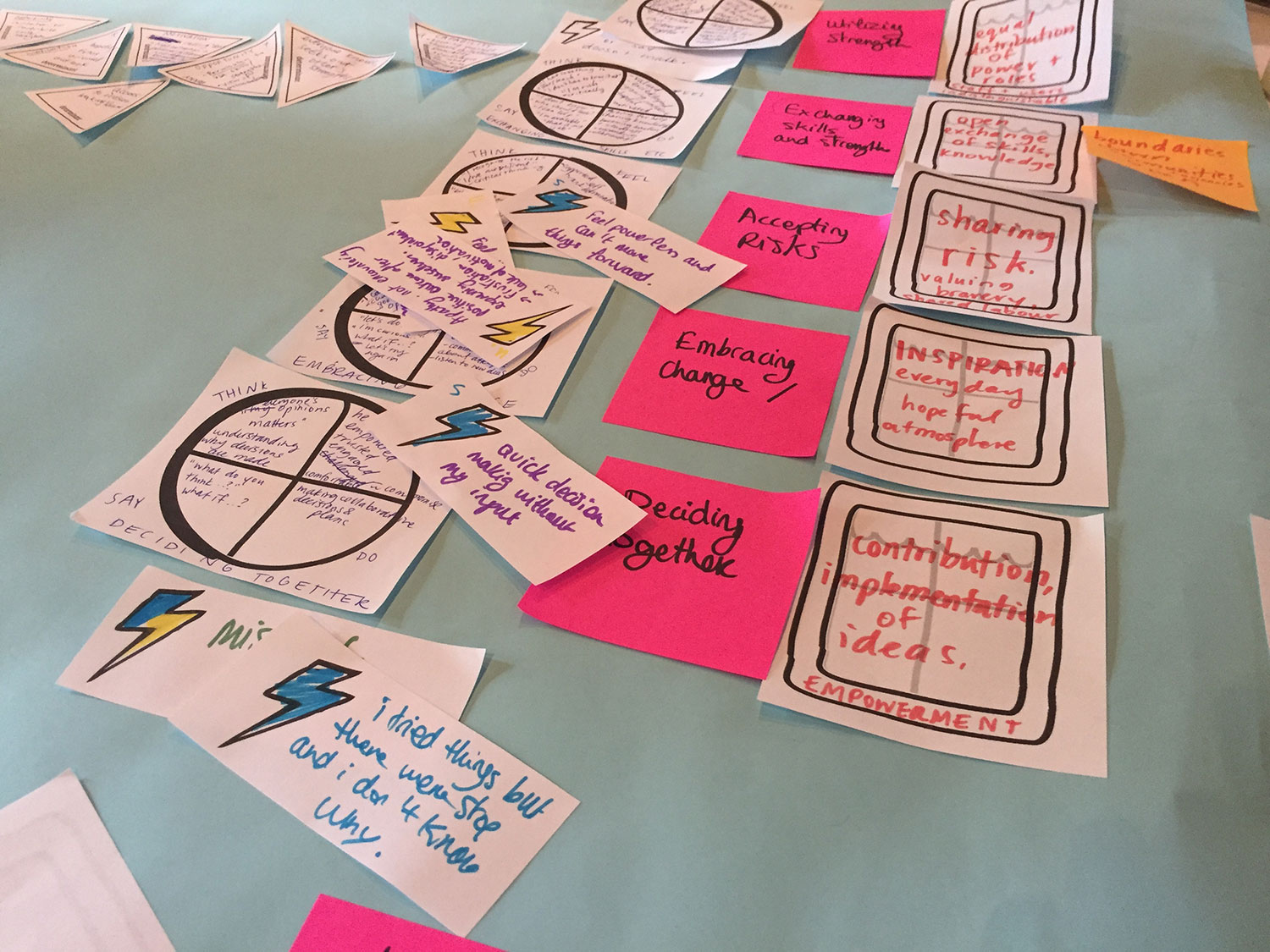

Not only do we flip from problems to outcomes, but we identify the factors that shape outcomes (the determinants) and co-design interactions that can shift those determinants. We find working at this level of granularity matters.

A couple of weeks ago, we were in Edmonton working with a committed group of social service providers. They were feeling a bit stuck. They had spent several months working on a proposal for ‘integrated case management’ to solve a system problem: a lack of coordination and inter-agency communication.

Challenge was, coordination wasn’t an expressed problem for the marginalized folks we spent time with, nor their desired outcome. What was desired? Feeling less shame. Now, there are a lot of factors that shape shame – such as self-worth, personal narratives, inter-personal interactions, perceived stigma, etc. A story collection tool that enables people to edit their stories and see themselves in a positive light (not simply as needy and helpless) could be an interaction to test. Such an interaction would be profoundly different from an assessment tool that enables the system to share information. Both might be labeled ‘integrated case management’ – but the starting point shapes purpose, functionality, and ultimately, impact.

Here’s where combining design and social science helps.

Social science gets us into our heads to disentangle assumed logics – how might interactions influence determinants, and how might those determinants get us to the outcomes we’re after? Design gets us out of our heads, and into our hands and bodies to see how those interactions might actually materialize for real people in a real context.

And yet design and social science are wholly insufficient. All of our logical thinking and all of our creative brainstorming occurs within a particular frame. We are constantly filtering information and ideas based on the implicit biases and underpinning values we hold. Until we can take the time to name the frames within which we are operating, we are liable to replicate variations of the current service system. We will get better safety nets – not trampolines. The disruptive innovations that are required to move towards such ambitious ideals as equality and agency start by accepting that people are worthy of more than a house and a meal.